Fossil fuel resources play a critical role in generating revenue for the Russian economy. Before the full-scale war in Ukraine, they accounted for about half of Russia’s export revenue, nearly a fifth of its GDP, and more than a third of its budget revenues. The export of Russian energy to Western countries was particularly significant. This is why great hopes were pinned on Western sanctions targeting Russia’s energy sector as a means to weaken its ability to finance the war. As uncertainty grows around scenarios for ending the conflict, the question of energy’s role in achieving peace becomes increasingly relevant, especially if negotiations fail to yield results soon. The focus is on factors such as the current decline in global oil prices, potential tightening of Western sanctions, and Russia’s ability to sustain the war amid falling export revenues from energy sales.

Resilience of Russian Energy and Economy

Since August 10, 2022, the EU has stopped purchasing Russian coal, followed by seaborne Russian oil from December 5, 2022, and Russian oil products from February 5, 2023. Additionally, the EU, G7 countries, and Australia introduced a $ 60 per barrel price cap on Russian oil starting December 5, 2022, and price caps on oil products ($ 100 for premium products and $ 45 for discounted products relative to crude oil) from February 5, 2023. Exceeding these caps means Russia cannot use Western shipping, insurance, and other services, which dominate global markets.

No sanctions were imposed on Russian pipeline gas, only on liquefied natural gas (LNG). However, the EU did not impose an embargo on LNG. Russia lost a significant portion of its European gas market due to its attempts to blackmail Europe by cutting off gas supplies and the Nord Stream pipeline explosions.

The EU and US also imposed numerous sanctions on Russian oil and gas companies, their subsidiaries, intermediaries, and individuals linked to the energy sector. The US and EU have periodically tried to prevent sanctions evasion, such as bypassing the oil price cap. These measures, combined with the consequences of Russia’s gas blackmail, have been painful for the Russian economy, but Moscow has consistently found ways to circumvent sanctions and continue funding the war in Ukraine.

The Russian energy sector and economy have proven far more resilient to sanctions than expected in the first year of the full-scale war. Several factors explain this. First, Western sanctions were designed with a key constraint: reducing Russia’s fossil fuel export revenues while maintaining Russian oil volumes on the global market to avoid sharp spikes in energy prices and a new global energy crisis. Second, Asian countries, particularly China, India, and Turkey, quickly and eagerly replaced Europe as the main buyers of Russian fuel, often at significant discounts.

This shift is evident in recent statistics. Between 2022 and 2024, Russian oil exports to China, India, and Turkey increased by roughly the same volume that exports to the EU, UK, and US decreased due to sanctions (see Figure 1). Notably, India, which purchased negligible amounts of Russian oil and oil products before the war, saw its imports rise 20-fold by 2023 compared to 2021. China, already a significant buyer in 2021, became Russia’s primary market by 2023.

Figure 1. Reorientation of Russian crude oil and oil product exports from West to East (export volumes)

Source: IEA data and author’s calculations.

According to CREA, Russia’s fossil fuel export revenue rose by 35% in the first year of the war (to € 356 billion) compared to 2021 (€ 264 billion). In the second year, due to falling energy prices and reduced supplies to Europe, revenue dropped to € 250 billion, below both the first year of the war and the last pre-war year. In the third year, revenue fell further to € 242 billion. Still, in 2024, Russia earned only 8% less from fossil fuel exports than in 2021, with oil revenues remaining above pre-war levels throughout the three years.

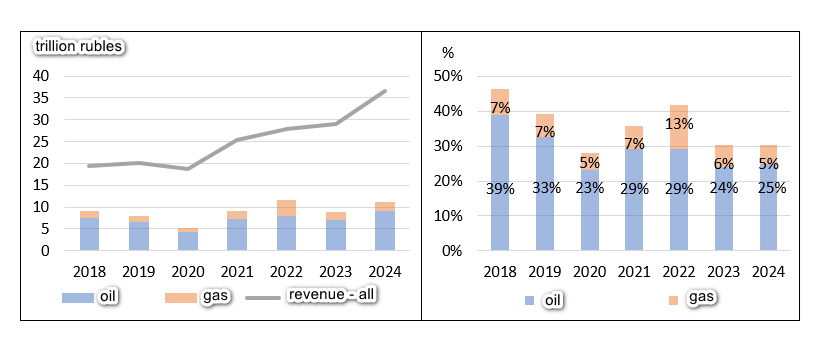

In 2023−2024, oil and gas accounted for 30% of Russia’s federal budget revenue, with oil contributing five times more than gas (see Figure 2). Before the war, oil and gas often played an even larger role, contributing, for example, 46% of budget revenues in 2018.

Figure 2. Russia’s federal budget revenue from oil and gas, trillion RUB and %

Sources: State Duma, Ministry of Finance, Bloomberg, and author’s calculations.

In 2023, the oil and gas sector accounted for 16.5% of GDP, and the coal sector for 0.5%. According to preliminary estimates by Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak, the fuel and energy complex contributed about 20% of GDP in 2024, compared to 17.4% in 2021.

Despite all sanctions, the role of fossil fuels in the Russian economy has barely changed over the three years of war. The share of the oil and gas sector in budget revenues has slightly decreased, but its absolute contribution to the budget has not declined, while other revenue sources have grown. This trend is likely to continue as the state actively seeks new revenue streams, such as through tax increases already underway.

Peace or New Sanctions

US President Donald Trump has repeatedly stated that the US aims to facilitate peace in Ukraine if both sides agree to a ceasefire. Otherwise, the US will impose economic sanctions. Ending the war in Ukraine is one of Trump’s key ambitions. Russia, however, shows little interest in peace. In early May, US Senator Lindsey Graham, backed by 72 other senators, proposed a bill to impose 500% tariffs on imports from countries purchasing Russian oil, oil products, gas, and uranium.

In early March, Trump indicated he was considering new sanctions and tariffs against Russia to achieve peace in Ukraine. By late March, he promised secondary tariffs of 25% to 50% on buyers of Russian oil if Russia obstructed peace efforts. However, in early April, Trump imposed tariffs on over 180 countries, with rates for some, like India (26%) and China (54%), already in the 25−50% range or higher. Thus, a 50% tariff on Russian oil importers is no longer a significant threat, but a 500% tariff could be. Notably, Russia was conspicuously absent from the list of countries targeted by Trump’s April tariffs.

The EU is also discussing new sanctions, including blocking Nord Stream 2, blacklisting ships in Russia’s shadow fleet, lowering the oil price cap, and more. The EU adopted its 17th sanctions package against Russia on May 16. Earlier this year, six EU countries—Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia—urged the European Commission to lower the oil price cap. In 2022, Poland, Lithuania, and Estonia argued the cap should be halved ($ 30 per barrel for crude oil), given Russia’s low oil production costs of about $ 20 per barrel.

Meanwhile, discussions in the US have occasionally raised the possibility of easing sanctions on Russia, though this seems unlikely without peace in Ukraine.

What Energy Shocks Could Force Russia to End the War

A significant tightening of Western sanctions could be one such shock. The US and EU will likely intensify efforts to push Russia toward ending the war, possibly through radical measures. So far, Western countries have adhered to the constraint of preventing large volumes of Russian oil from disappearing from the global market. However, if this ceases to be a priority, the US and EU could devise mechanisms to force China and India to reduce Russian oil purchases (e.g., through stringent US secondary sanctions) or drastically increase Russia’s energy export costs (e.g., by sharply lowering the oil price cap while cracking down on sanctions evasion). Such a scenario is uncertain, with questions remaining about exemptions, delays, and enforcement effectiveness.

Another shock could be the ongoing decline in oil prices, now roughly at pre-war levels—10% lower than a year ago and 40% lower than during the 2022 energy crisis triggered by the war. The Russian government has lowered its oil price forecast from $ 69.7 to $ 56 per barrel. Due to falling oil prices and a stronger ruble, Russia revised its federal budget revenue forecast downward by 4.5% and raised its expected budget deficit from 0.5% to 1.7%. The budget deficit reached 1.5% in the first four months of 2025, driven entirely by lower oil and gas revenues. While these deficit levels are not critical, a significant and sustained drop in oil prices—to $ 40 per barrel or lower—could pose a threat. However, such a scenario is not currently expected, and global oil exporters would likely act to raise prices if it occurred.

Other energy sector shocks that could threaten Russia’s economic stability enough to force an end to the war are hard to imagine. One unlikely scenario could involve China and India voluntarily joining some sanctions. Western countries have repeatedly tried to enlist their participation, but both nations prefer to capitalize on cheap Russian fuel for their economies.

Finally, a «black swan» event cannot be ruled out. For instance, few predicted the Soviet Union’s collapse during Gorbachev’s early years (1985−1987). Yet by 1991, the USSR dissolved, partly due to events like the 1989 miners’ strikes—the first open mass strikes in the country. Ironically, Russia’s coal industry is now in crisis due to the EU’s 2022 coal embargo and logistical challenges in redirecting exports to Asia amid falling coal prices. Falling oil prices in the 1980s also exacerbated the Soviet Union’s structural economic issues, contributing to its collapse.

Current Western energy sanctions primarily undermine the long-term competitiveness of Russia’s energy sector by isolating it from Western technologies, investments, and markets. Russia is increasingly reliant on China as a long-term partner, but China, while benefiting from cheap Russian fuel, has no intention of becoming dependent on Russia and treats it as one of many partners. However, Russia’s long-term economic risks have been overshadowed by short-term priorities.

In 2022−2023, there was hope that economic pressures could force Russia to end the war, but these hopes are fading. India and China have no intention of abandoning cheap Russian fuel, and Russia can supply oil to them despite Western restrictions. Russia has gained significant experience in evading sanctions. Redirecting gas and coal flows is harder than oil, but these fuels generate far less revenue. Russia’s economy has shifted to a war footing, with millions of jobs now tied to the war effort, including not only combatants but also workers in defense industries and related sectors. The state is finding new revenue sources, such as tax hikes, and a population subdued by repression, propaganda, and historical experience is willing to overlook declining living standards and war losses.

This enables the Kremlin to confidently continue the war and perhaps even fear its end. The longer the regime recognizes these dynamics, the more assured it becomes of its survival. After all, if the war ends, it’s unclear what could replace it as the driving force for the country’s development. In a quarter-century, this regime has found no other purpose for its existence.